Hello there, yuzu fans!

We are very excited to share the news of another major feature release.

Thanks to the efforts of our dev Blinkhawk, yuzu now supports Multicore CPU emulation.

Hop right in, to read more about it!

In Greek mythology, Prometheus is a Titan that aided humanity by teaching how to make fire.

In modern society, it symbolizes the strive for scientific knowledge.

The Prometheus Project is about that - the journey to new emulation techniques.

Since we cannot really show performance boosts in pictures, here is a video by BSoD Gaming that takes you through all the improvements.

What is Multicore CPU emulation?

As many of you might know, yuzu is considered a HLE (high level emulation) emulator.

This means that instead of running the real Switch OS (known as Horizon), yuzu has recreated its own version of the OS, built entirely from the ground up.

Like your PC, the Switch has multiple cores (4, actually), and the Horizon OS can run multiple tasks in parallel on these cores using a kernel construct known as a thread.

However, due to limitations of our old kernel design taken from Citra, yuzu was actually emulating this behavior using a single core on your host PC!

This had led to an absurdly high CPU requirement for users.

So, what is "Multicore CPU emulation"?

Put simply, instead of emulating the CPU on a single thread yuzu will now emulate the CPU using multiple threads; 4 to be precise - one for each Switch CPU core.

Although it might sound simple or easy, it is nevertheless the biggest undertaking this project has seen up until now.

yuzu CPU emulation

yuzu’s initial CPU emulation and kernel were heavily based on Citra’s.

The kernel emulated the external behavior of the Switch’s kernel but vastly differed from the Switch OS.

Instead of saving contexts and switching from one guest thread to another within the kernel, we used a mechanism within Citra’s kernel that emulated the same behavior but with a complex system of stops and callbacks.

Not only that, but in the typical tradition of previous emulators, yuzu used something called a cycle timer.

A cycle timer is a mechanism to emulate time on consoles by counting each guest instruction executed and adding it to global CPU ticks.

These ticks can then be transformed into time units like nanoseconds by using the guest’s CPU frequency.

Drawbacks

Citra’s model was perfectly fine for single core emulation. It was accurate, simple, and worked perfectly for the 3DS as it used only one of its two cores for apps/games. However, in the case of yuzu, this wouldn’t hold true.

The Switch is a much more complicated and modern system that pushes 4 CPU cores, where 3 are used for apps/games. Not only that, but the scheduling is more robust and can be used in some more interesting and more complicated ways. Using Citra’s model for scheduling was all possible in yuzu but it had a few flaws of its own:

- The code didn’t match the Switch OS and even though it had the same behavior, it was hard to keep track of changes and replicate them.

- The code was very complex as there was a callback for everything and was hard to maintain.

- This model would be extremely hard to run on multiple host threads.

Prometheus

You might’ve heard rumors and whispers about this in the community recently.

Prometheus is the internal codename for this feature’s development and it is a total rework of three things:

- Kernel scheduling

- Boot management

- CPU management

Prometheus aims to ensure that emulation behaves the same as on the Switch while matching the code with the Switch’s original OS code.

And, as a by-product, host multicore support using host timing has been added to yuzu.

Host timing is just yuzu using the host’s (user’s) internal clock for timing.

The multicore feature of Prometheus is a beast in terms of thread handling.

Originally yuzu used at best 2 threads: one for the CPU and one for the emulated GPU.

Technically we also use a thread each for the UI, logging, the host GPU driver, and the host audio driver, but let’s ignore them for the time being.

With multicore, there are now 6 threads in use: four for the CPU, one for the timer, and one for the emulated GPU.

It is worth noting that CPU core 4 is rarely used.

Of these 6, effectively 5 threads have considerable use but not all will be running constantly.

Planning

Prometheus was a big undertaking that was set in two phases: planning phase and development phase.

The planning phase was all about studying our current setup to make it work under this new scheme.

This happened roughly over 8 months, and was mostly just research and brainstorming.

During this phase, Blinkhawk encountered multiple challenges and considerations for development. He started studying other emulators that already did multicore emulation such as Cemu, RPCS3, and Ryujinx.

These emulators all differed in their approaches to multicore. Some used Fibers for guest threads, 1:1 guest-host kernel threads, cycle timing, or host timing. In computer science, Fibers are lightweight threads of execution (Wikipedia).

For yuzu, we initially planned to use Fibers and cycle timers. We chose Fibers over kernel threads because changing a Fiber is at worst 50 host CPU cycles, whereas a kernel thread can be thousands of cycles and there’s no guarantee that the host OS will start running it right away.

In the case of cycle timers for yuzu multicore, they ended up being quite a pain. Cycle timers have many advantages over host timers:

- They are deterministic,

- They don’t leak the host state, and

- They always advance for every instruction that Cycle timers are run.

We tried many theoretical models for multicore cycle timers and they all were pretty hard to set up while still having flaws. Sadly, cycle timers don’t work too great for multicore settings, because it is very hard to keep all the cores advancing at the same pace and to emulate idling accurately. For all these reasons, we opted for host timing instead.

Bayonetta 2

Development - Issues

Development started on February 1st of 2020. The first thing Blinkhawk did was to implement Spinlocks, Fibers, and host timing. Afterwards, he went ahead with the massive overhaul.

As he started the overhaul, the first issue he encountered was that for some reason yuzu was creating and destroying JITs (just-in-time compilers). Thus, whenever we resumed code from a guest thread and it went back to the JIT, it would hard crash. This was fixed by caching the JITs depending on the state of the page table, instead of creating a JIT every time. This way we could also avoid creating more JITs than necessary.

The second issue occurred on booting the first homebrew on multicore, where we found that guest vsync was messed up. By redesigning the server session we were able to identify the cause and fix it.

Here is where things started getting interesting.

Blinkhawk implemented Condition Variables and Mutexes, which are the base syncing mechanisms in any multithreaded environment, and found an issue with how our JIT functions.

Our JIT was heavily designed to work like Citra’s and it expected that on any SVC (Supervisor call) call to kernel, the code returned back afterwards.

Under the new architecture, a thread could easily call an SVC and be paused there, while another thread started running on that same JIT, thus causing a conflict.

The easy solution was that instead of making a JIT per core, we would make a JIT per thread.

This solution, however, costs us additional memory usage.

After fixing these issues, we were finally able to boot Super Mario Odyssey on multicore, but many games were still soft-locking due to an old bug we thought eradicated: Mutex Corruption.

Mutex Corruption happens due to issues with exclusive memory handling in ARMv8.

As it turned out, dynarmic had to be modified to fix it.

After looking into it, Blinkhawk realized exclusive memory in dynarmic was prone to a race condition when the exclusive address was written by a non-exclusive write. The solution was to save the current value on exclusive read and then atomic exchange it with a new value on exclusive write. By fixing this, most of the games were able to go in-game and many of them were fully playable.

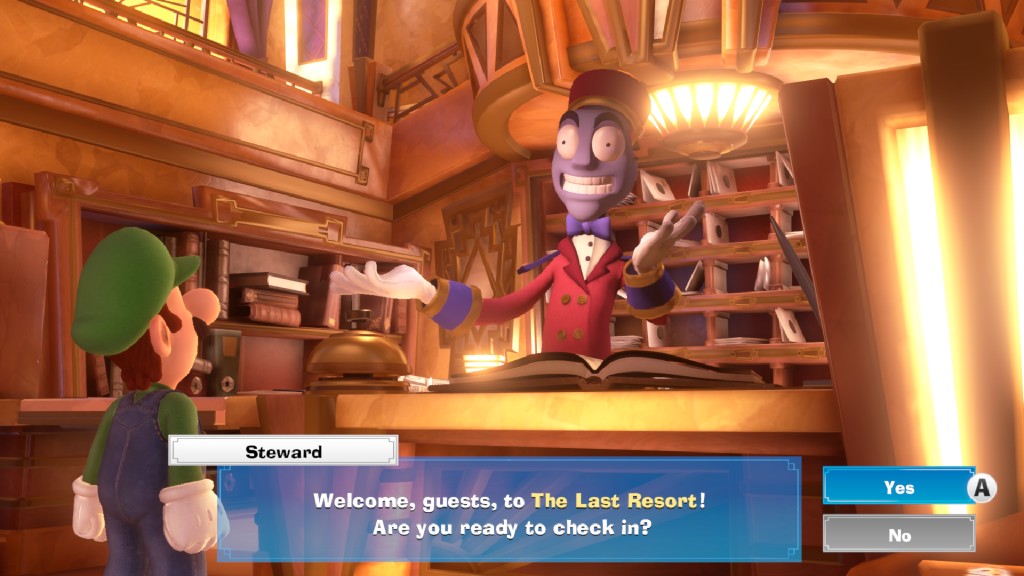

Two games had interesting bugs on multicore: Luigi's Mansion 3 & Hyrule Warriors.

Luigi's Mansion 3 had an issue in which two threads, A & B, were running on cores 0 and 1 and after some scheduling, B was rescheduled to core 0 and A to core 1.

But a thread cannot start running on a new core until it is liberated (freed).

So core 0 scheduler was holding A and waiting for B to be freed, while core 1 scheduler was holding B and waiting for A to be freed, thereby causing a deadlock.

The solution was that instead of exchanging threads on scheduling switch, we free the current thread and switch to an “intermediary” thread and then from there proceed to the next thread.

Hyrule Warriors had an issue that was caused by host timing.

Our host timing implementation was based on Cemu’s approach and used x64 architecture’s hardware timer directly.

This timer is way more accurate than ARMv8’s hardware timer present in the Switch.

The game soft locked at a point because a thread infinitely looped on a TimedWait of 30 nanoseconds.

This function did some time calculations and later checked with the current time.

If the timeout wasn’t reached at that moment, an SVC was called which paused the thread for some time and let the next thread run, effectively causing a yield.

In the Switch’s hardware, the timer’s accuracy isn’t too great and a TimedWait of 30 nanoseconds always resulted in the thread calling the SVC.

Our host timer, however, was way more accurate and that function would never call the SVC.

The solution, ironically, was to reduce the accuracy of our host timer a bit, to better match actual hardware.

Another interesting challenge was implementing pausing/resuming in multicore. As you know, you can pause and resume yuzu in our current versions. This was simple before because emulation occurred in steps and you just had to stop on the next step. But on multicore, emulation is continuous and unmanaged in the same sense.

Thus, implementing this was very hard due to how multicore scheduling worked. The original solution was to modify scheduling to support it but that proved very complicated to do. After a while, we figured out a pretty easy solution without having to modify anything. We would create a kernel thread for each core and make that kernel thread pass control from and to the CPU Manager to the emulation.

What to expect with games?

Many of you may be eager for multicore but have in mind that there are other bottlenecks as well.

Not every game utilizes multithreading effectively and makes the most use of the Switch’s CPU.

Some games, like Super Mario Odyssey, barely use cores 1 & 2, by doing all processing in core 0, effectively making them gain nothing from multicore.

However, games like Breath of The Wild see some performance boost but are still bottlenecked by the emulated GPU.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

The emulated GPU depends on four things:

-

Your CPU’s single-core speed. A single host CPU core translates all the commands from guest GPU (Switch) into host GPU (User) commands. So, having a CPU with great single-core speeds is most beneficial.

-

Your GPU Bus Speed. yuzu heavily relies on the bandwidth available in the GPU bus. This is the speed at which data is uploaded to and from your GPU and this varies depending on PCIe generation and allocated lanes.

-

The quality of your GPU drivers. AMD’s drivers for OpenGL are terrible while NVIDIA’s are great.

-

Your host GPU itself, be it NVIDIA, AMD, or Intel.

Lastly, be aware that RAM speed, amount of RAM, and the type of processor in your system, will also influence your experience. The initial release may use additional memory (100mb to 3Gb depending on the game). We are currently stability-testing a fix for this additional memory usage.

Current Known Issues

Getting multicore to run perfectly is a big deal and in our internal testing we found that audio can be slower in multicore.

Activate Audio Stretching to mitigate the issue.

If you come across any softlock or bug that is not present in mainline but present in early access, notify us and include the following data with it.

* Game name

* Version of the game

* Game savefile

* Steps to reproduce the softlock

* Whether the softlock is random or consistent (always happens in the same spot)

Please consider supporting us on Patreon!

If you would like to contribute to this project, check out our GitHub!

Advertisement

Advertisement